The most romantic, and yet the most tragic love story that William Shakespeare ever wrote is indisputably that of Romeo and Juliet. Most of us have seen this masterpiece interpreted either on stage or on screen. And some of us have seen it several times. And yet we are always drawn to this piece and are ready to see it one more time.

The most romantic, and yet the most tragic love story that William Shakespeare ever wrote is indisputably that of Romeo and Juliet. Most of us have seen this masterpiece interpreted either on stage or on screen. And some of us have seen it several times. And yet we are always drawn to this piece and are ready to see it one more time.Right now, you have an opportunity to see once again another interpretation of this ageless love story, this time on stage right here in Montreal. This ballet, set to the music of Sergei Prokofiev, is presented by Les Grands Ballets Canadiens at the Théâtre Maisonneuve at the Place-des-Arts.

If you are in a mood for romanticism, you might not find it in this staging of the famous love story. Some of the elements used to create a heightened romantic mood – luscious colours, elaborate period costumes and seductive lightening are not present in this piece. Neither is present the precise, traditional choreography with a set of effective means of expressing emotions which communicate to the public with ease and immediacy.

Let us momentarily contemplate the subject of ballet.

Until recently, the ballet of the past had gone unchanged for a very long time, trying to preserve the purity of its traditional forms of expression which had the power to communicate emotions with easily understood clarity. In addition, the traditional ballet was concerned with the gracefulness of movements which effectively created an overall poetic, dignified, splendid, and even noble effect.

Let us be honest, can we call our present times noble, poetic and dignified? In the world where in order to be noticed you have to be “chic”, “with it” and “cool”, the old ballet values are no longer understood or appreciated.

It has been a couple of decades now that the traditional ballet has found itself at odds with the present reality, and has even been perceived as outmoded. New artistic forms from modern and jazz dance have been steadily seeping into ballet. Yet let’s hope that the purely traditional ballet would not die completely, and that it will be preserved and staged periodically as an alternative to the mixed style that is currently in vogue and is taking over the ballet.

So how is current interpretation of the famous love story Romeo and Juliet by Les Grands Ballets Canadiens different?

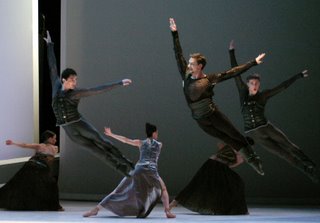

This Romeo and Juliet is not a period mis-en-scène. There are no lush stage sets, nor colourful costumes or lights. As a matter of fact, the decor by Ernest Pignon-Ernest can be referred to as minimalist. He achieves the definition of the space with several movable white screens, which, depending on the scene, change colour by means of spot lights. But do not expect any bright and vibrant colours such as reds or greens. The pallet ranges from white to black, passing though various degrees of grey and beige with a tinge of ochre. As for the costumes, designed by Jerome Kaplan, they match the minimalist colour palette of the mis-en-scène. The only exception is a luscious, shimmering gold dress of Juliet which she wears in a masquerade scene where she first meets Romeo.

What might be the reasons for the removal of colour and of blossoming elements from this interpretation of Romeo and Juliet? (As a matter of fact, you will not even see the traditional balcony from which Juliet calls dreamily to her lover.) Is the stern decor chosen in order to zoom the spectator’s attention to the sculptural quality of the dance? If that is the case, could this explain the color scheme of this production - that of metals, plaster and clay, which are the traditional sculpture materials?

The choreographed movements in this ballet are purely sculptural. Each grouping of characters, each pas-de-deux, creates a sculpture in space. The movements own the space. The space is constantly restructured with bodies and limbs, and is permeated with visceral energy.

What you see on stage is sculpture in motion. Each dance is choreographed in such a way as to restructure with every movement the three-dimensional space.

By all means, go and see this ballet. You might find yourself enchanted with the Prokofiev’s music, and with the kaleidoscopic movements on stage. And above all, you will be once again reminded of the great Shakespeare’s genius, which has fascinated us through many centuries.

Photo above

by Sergei Endinian

Romeo and Juliet

Dancers of Les Grands Ballets Canadiens